tl;dr update: I submitted a bug report about this issue to the WordPress Trac, it was fixed in 6.7.1, and I was even credited as a contributor to that version. Now on with the post…

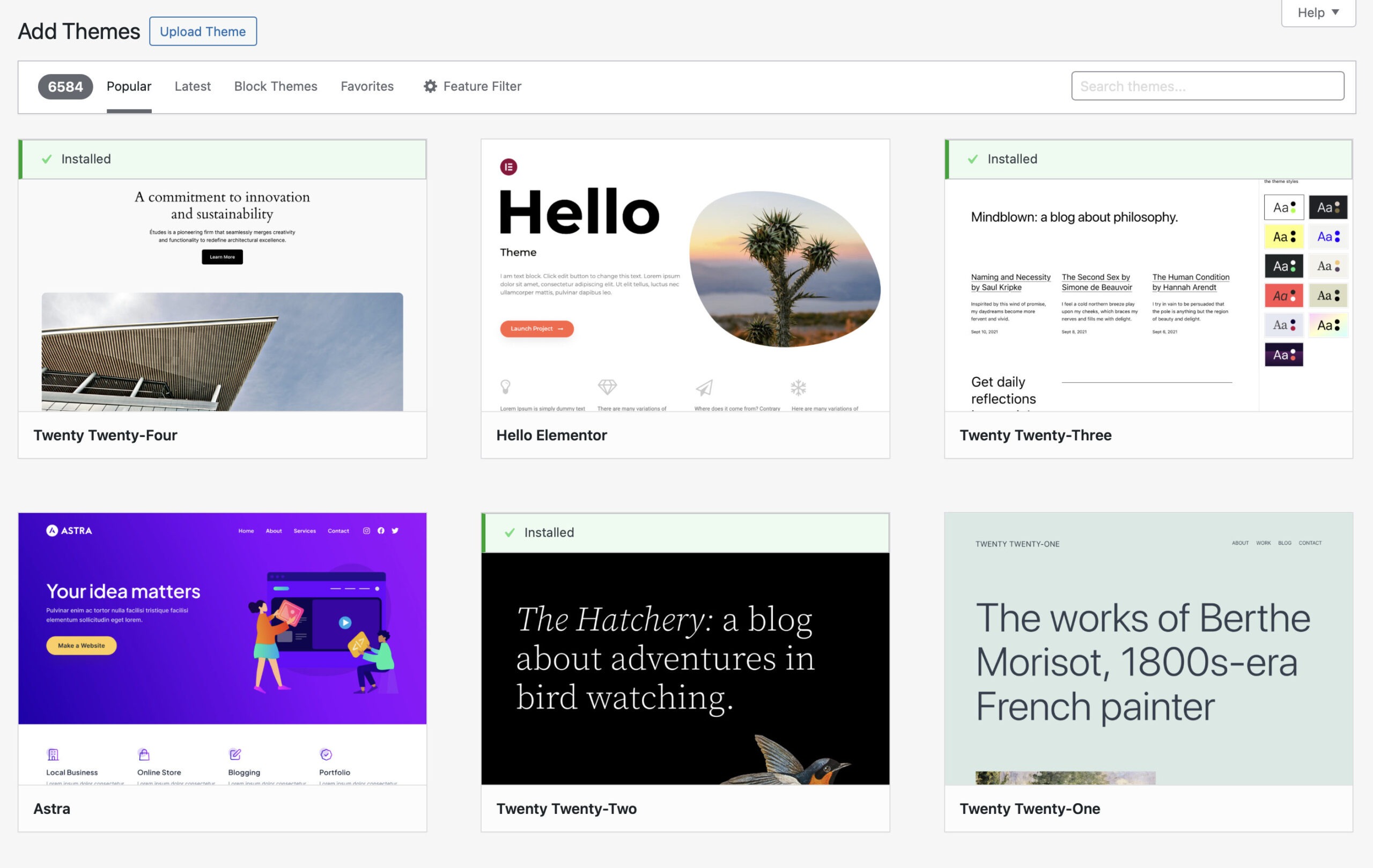

Look at this image:

Now look at this one:

What if I told you those were the same image? Well… I mean… they’re not. Obviously. But they’re supposed to be. They were both the same image when they were on my computer. The same exact file. But I uploaded them to this page in two slightly different ways, and that made all the difference.

The one on top — the screwed-up one — I placed by inserting an Image block in the WordPress Block Editor, and then clicking the Upload button in that block, navigating my hard drive, and locating the image. The one on the bottom, I placed by again inserting an Image block, but this time I just dragged the image from a Finder window into the Safari window. WordPress supports drag-and-drop uploads.

Looking “under the hood,” I discovered that the file on top was somehow getting converted to Apple’s “High Efficiency Image Format,” HEIC (the reason for the C instead of an F is something I’ll leave to the Apple podcasters). WordPress just added HEIC support in version 6.7, which was released this week. Since browsers (other than Safari, I assume) can’t display HEIC images, WordPress automatically converts uploaded HEIC files to JPEG. And that’s why these two images look different. JPEG doesn’t support transparency, so the areas that were transparent in the original PNG got flooded with the nearest available colors1.

But, why should the results of these two upload processes be any different?

Well, after starting in the WordPress Support Forums and then moving over to the Make WordPress Core Trac and finally searching until I stumbled upon a year-old, barely active thread on the Apple Developer Forums, I discovered that Safari has a bug — I mean it has to be a bug, right? — where, if a file upload input field says it accepts HEIC format, Safari automatically converts the uploaded file to that format, apparently with no option not to do that. (I looked around all of the settings, even the developer ones, and didn’t see anything about this “feature” at all.)

And sure enough, WordPress 6.7 is a bit haphazard with its “support” of HEIC uploads, which made it easier to confirm the cause. There are two ways, generally speaking, that WordPress handles file uploads: the browser upload, via an <input type="file"> HTML field, and a JavaScript/AJAX/React/whatever drag-and-drop option.

The <input type="file"> field in the Image block of the Block Editor has added HEIC support via the accept="image/heic" attribute. But the input field in the old school Media Library upload page has not been similarly updated. (It’s become a fact of life in the WordPress world that most of the core team’s attention is on Block Editor stuff these days, and older features get ignored.) Uploading images in the Media Library does not do the conversion. Likewise, whatever exactly is going on with the drag-and-drop method also does not involve the accept="image/heic" attribute that causes Safari to do its mischief.

Unfortunately, it looks like the only “solution” at this point would be for WordPress to do a browser sniff and remove the accept="image/heic" attribute if the browser is Safari. The only reason that was explicitly added was to get Chrome to support HEIC uploads; as I understand it, Safari would support them regardless, but explicitly declaring HEIC support is apparently what triggers Safari to make the conversion.

So, practically speaking, Safari users who want to upload PNGs to their WordPress sites just need to be sure to only upload via drag-and-drop, or the Media Library.

(I haven’t tested, but I suspect JPEG uploads are likewise getting converted to HEIC and then back to JPEG, which probably results in a reduction of image quality.)

Side note on how I discovered this in the first place: Two days ago I was writing another blog post somewhat critical of Apple, and I found when I was trying to upload a screenshot of a window from my Mac — Mac screenshots are saved as transparent PNGs — the transparency was turning black. I was so driven to distraction over the situation that I barely managed to finish writing the post.

1 Saying those areas are flooded with color is an oversimplification. It looks like the color of each pixel is being determined consistently with how PNG compression works.