I hate Elementor.

If you don’t know what Elementor is, good. If you do, you probably either hate it too, or else you’ve never used WordPress without it. (And even if you haven’t ever used WordPress without it, you still might hate it.)

In my experience, Elementor is hot garbage, and it makes the overall WordPress experience bad.

It’s not just Elementor. There are several “page builder” plugins for WordPress, and they’re all terrible. Divi, WP Bakery, Beaver Builder, etc. They all deviate wildly from the way WordPress is intended to work. Since 2018 WordPress has had the Block Editor (a.k.a. Gutenberg) built-in, which is essentially a page builder itself. Now that Gutenberg has matured enough to be useful, those other page builders are completely unnecessary.

Among the page builders, I think Elementor is the worst. Why? Mainly because of its ubiquity.

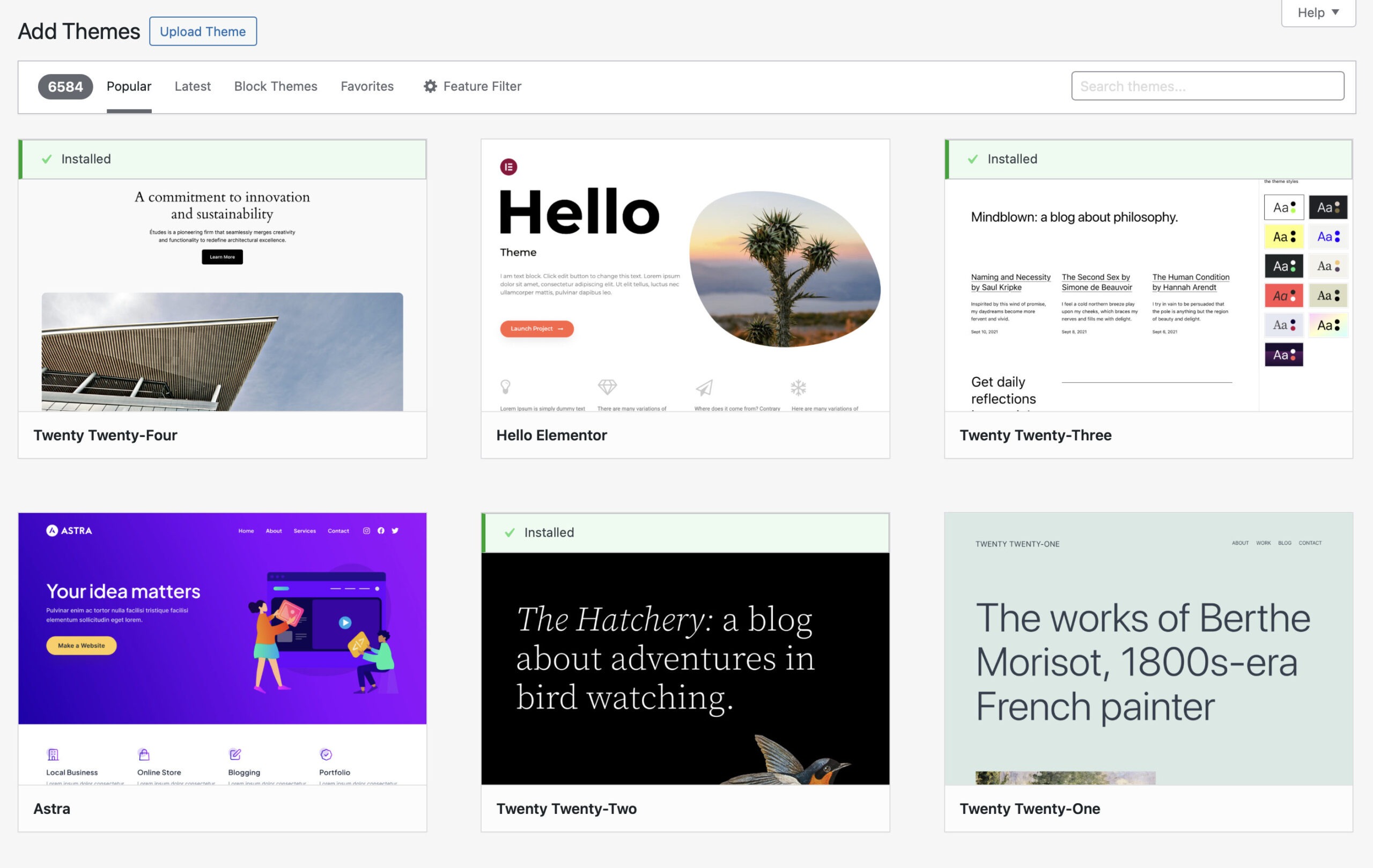

Elementor is extremely popular, in part because there’s a companion theme/gateway drug called Hello Elementor. It is the most popular third-party WordPress theme, as evidenced by its lofty position at the top of the WordPress theme download screen, surrounded by the official annual themes and one other third-party theme, Astra. (I actually really like Astra, because for the most part, it does things the WordPress way.)

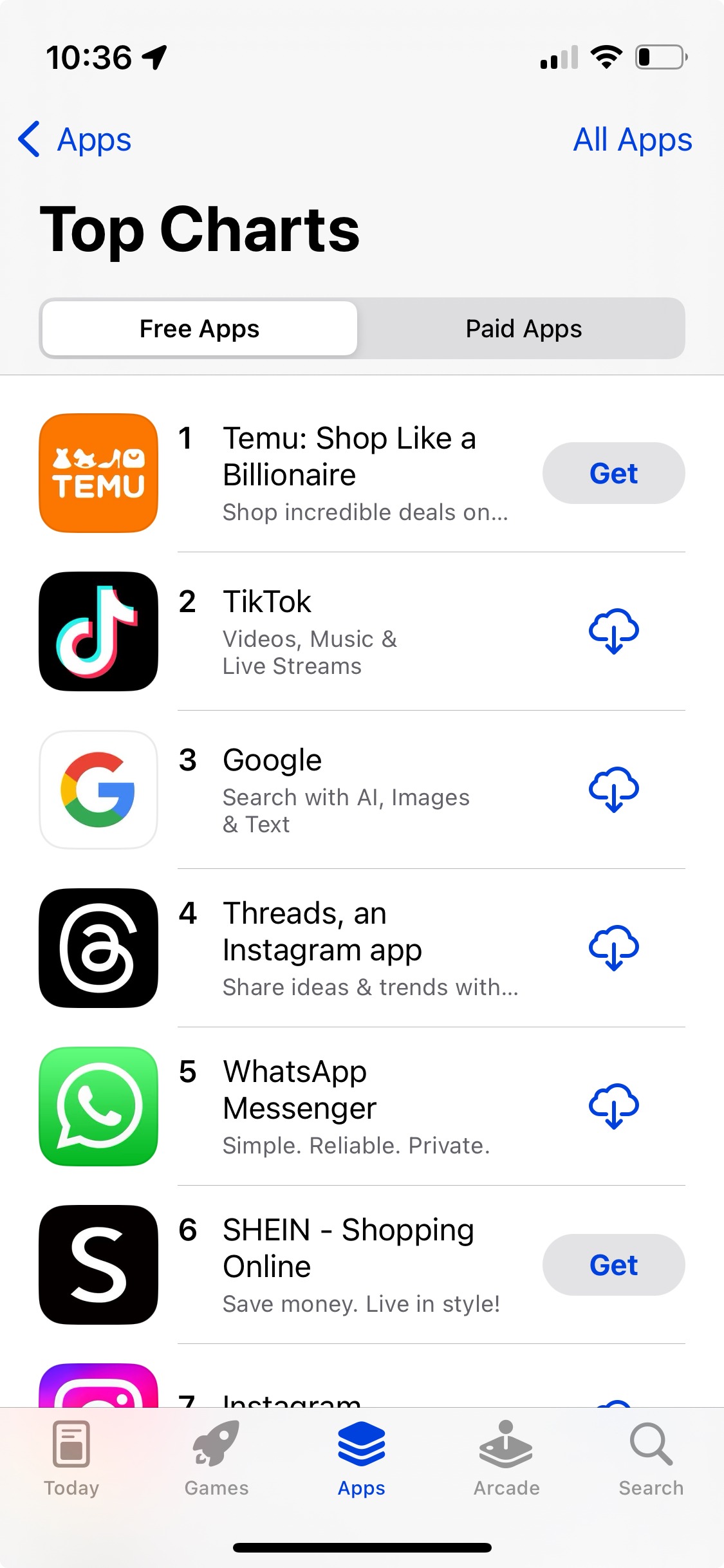

Why is Hello Elementor so popular? Presumably people do like it. But I think it is also an example of what I would call the popularity feedback loop. It’s a natural, and harmful, side effect of a page like this, also commonly seen on e-commerce sites.

If you sort things by popularity, with the most popular items at the top, those are what people are going to see first. And most people don’t want to spend a lot of time considering options. They may trust popular opinion, or they may be too impatient to consider their options carefully, or they may just not care at all. So they click on the first thing that catches their attention, thereby making the popular thing even more popular, and dooming less popular options to oblivion, regardless of their quality.

The people choosing to default these lists to ranking by popularity may think they’re making an objectively straightforward choice, but they’re not considering how the popularity feedback loop might have much more of an effect on the rankings than quality, because they’re falsely assuming that people are making careful, rational choices.

There’s a large segment of the developer world that tries to avoid making “opinionated” decisions. But that’s a delusion. Every decision is opinionated. I would prefer to lean into it. Make the default a “recommended” list of options that have been evaluated by knowledgeable editors. Granted, that’s a lot more work, and is still subject to personal opinion and taste, but it could weed out the popular-but-garbage options that inevitably float to the top.

There’s another reason in this specific context why it matters. New users don’t understand the WordPress ecosystem. They don’t know about third-party themes and plugins. They don’t know what does or does not adhere to “the WordPress way.”

So, a new user comes in and wants to pick a theme for their site. Their eye is drawn to the Hello Elementor screenshot, which has been carefully designed to be attention-grabbing, especially compared to the rather pedestrian appearance of the official themes.

That’s all fine in and of itself. Third-party themes are great! But when you activate the Hello Elementor theme, it immediately starts prompting you to install the Elementor page builder plugin as well. If you’re not an experienced user, what are you supposed to do with this? You probably install it, of course. And now you’re in page builder land. It’s not WordPress anymore. The experience is completely different.

But what is it about page builders that’s so bad? (And this part really applies to Gutenberg to a large extent as well.) They’re supposed to be making it easier to design your web pages, right? Well… there’s only so much you can do to make designing a web page easier. There’s no way to deal with things like margins or padding without understanding what margins and padding are. The page builders end up being CSS GUIs. Maybe you’re not writing the code, but you still need to know the concepts to get anywhere. So you end up either creating a convoluted mess, or at best you do learn the concepts, but in a compromised way, that is inextricably tied to that page builder plugin. It’s lock-in.

I could go on, but I think there are two main ways to address the problem of the popularity feedback loop, at least as it applies specifically to WordPress themes, but also more generally:

- Don’t default to a “most popular” view. I know it takes a lot more work, and is a lot more subjective, but the best default would be a “recommended” view. Some editorial decisions need to be made. Consider popularity, of course, but also consider context. Which themes are the best for a newcomer? Which ones offer the most pure WordPress experience?

- Make the “most popular” list conditional. This is a more automated version of #1. Maybe you don’t have a carefully curated editorial list of recommendations, but at the very least, determine some criteria that can restrict what shows up in the list. For starters, maybe a theme cannot load with an admin notice pushing users to install a plugin. Would Hello Elementor be such a problem if it didn’t immediately lure new users into installing a page builder plugin too? Probably not.

Ultimately, I have my own selfish motivations in all of this. I develop a number of WordPress plugins myself, and I need to provide user support for them. And a significant percentage of my overall user support load — I would say it’s around 15-20% — is around conflicts with Elementor.