Update (April 12, 2023): If you’re looking to use my RSS Enhancements for The Events Calendar plugin in conjunction with MailChimp in 2023, please note that MailChimp has changed up how they handle RSS feeds in campaigns. A user of the plugin provided some insight on the changes over in the WordPress Support Forums.

This one’s a doozy. I have a client who is using The Events Calendar, and they want to automate a weekly email blast listing that week’s events, using MailChimp.

The Events Calendar automatically generates an RSS feed of future events, inserting the event’s date and time in the RSS <pubDate> field. And MailChimp offers an RSS Campaign feature that can be scheduled to automatically send out emails with content pulled in from an RSS feed.

So far so good. But there were a few things the client wanted that were missing:

- Show exactly a week’s worth of events. The RSS feed just pulls in n events… whatever you have set in Settings > Reading > Syndication feeds show the most recent.

- Display the event’s featured image. Featured images aren’t included in WordPress RSS feeds, neither the default posts feed nor The Events Calendar’s modified feed.

- Show the event’s location. This is also not pulled into the RSS feed at all.

To make this happen, I had to first get the RSS feed to actually contain the right data. Then I had to modify the MailChimp campaign to display the information.

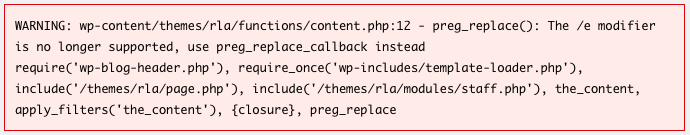

The problem in both cases surrounded documentation. RSS, though it’s still widely used, is definitely languishing if not dead. The spec is well-defined, but there’s not a lot of good information about how you can customize the WordPress RSS feed, and even less about how to customize The Event Calendar’s version. What info I could find was generally outdated or flat-out wrong — like the example in the official WordPress documentation (the old documentation, to be fair) that has at least three major errors in it. (I’m not even going to bother to explain them. Just trust that it’s wrong and you shouldn’t use it.)

Now that I’ve put in the hours of trial and error and futile Googling, I’ll save you the trouble and summarize my successful end result.

Problem 1: Show a week’s worth of events in the RSS feed

It took a surprising amount of effort to figure out how this is done, although in the end it’s a very small amount of code. Part of the problem was that I was not aware of the posts_per_rss query parameter, and therefore I wasted a lot of time trying to figure out why posts_per_page wasn’t working. Maybe that’s just my dumb mistake. I hope so.

I also spent a bunch of time trying to get a meta_query working before I realized that The Events Calendar adds an end_date query parameter which makes it super-easy to define a date-based endpoint for the query.

You need both of these. Depending on how full your calendar is, the default posts_per_rss value of 10 is possibly not enough to cover a full week. I decided to change it to 100. If this client ever has a week with more than 100 events in it, we’ll be in trouble… probably in more ways than one.

Here’s the modification you need. Put this in your functions.php file or wherever you feel is appropriate:

// Modify feed query

function my_rss_pre_get_posts($query) {

if ($query->is_feed() && $query->tribe_is_event_query) {

// Change number of posts retrieved on events feed

$query->set(‘posts_per_rss’, 100);

// Add restriction to only show events within one week

$query->set(‘end_date’, date(‘Y-m-d H:i:s’, mktime(23, 59, 59, date(‘n’), date(‘j’) + 7, date(‘Y’))));

}

return $query;

}

add_action(‘pre_get_posts’,’my_rss_pre_get_posts’,99);

What’s happening here? The if conditional is critical, since pre_get_posts runs on… oh… every database query. This makes sure it’s only running on a query to retrieve the RSS feed and, specifically, The Events Calendar’s events query.

We’re changing posts_per_rss to an arbitrarily large value — the maximum number of events we can possibly anticipate having within the date range we’re about to set.

The change to end_date (it’s actually empty by default) sets a maximum event end date to retrieve. My mktime function call is setting the date to 11:59:59 pm on the date one week from the current date. You can just change the 7 to another number to set the query to that many days in the future. There are a lot of other fun manipulations you can make to mktime. Check out the official PHP documentation if you’re unfamiliar with it.

Every add_action() call can include priority as the third input parameter. Sometimes it doesn’t matter and you can leave it blank, but in this case it does matter. I’m not sure what the minimum value is that would work, but I found 99 does, so I stuck with that.

Problems 2 and 3: Add the featured image and event location to the RSS feed

RSS is XML, so it has a syntax similar to HTML, but with its own specific tags. (And with XML’s much stricter validation requirements.) WordPress uses RSS 2.0. This can get you into trouble later with the MailChimp integration, because MailChimp’s RSS Merge Tags documentation gives an example of the RSS 1.5 <media:content> tag for inserting images, but you’ll actually need to use the <enclosure> tag… which MailChimp also mentions, but not in conjunction with images. Still with me?

All right, so the first thing we’re going to need to modify in the RSS output is the images. And don’t believe that official WordPress documentation I mentioned earlier. It. Is. Wrong. My way works.

The next thing we want to do, and we’ll roll it into the same function (because I want to contain the madness), is to add in the event’s location. There’s no RSS tag to account for something like this. You could add it to the <description> tag, although I found that since the WordPress rss2_item hook seems to be directly outputting RSS XML as it goes, I didn’t track down a way to modify any of the output, just add to it.

There’s another standard RSS tag that WordPress doesn’t use — or at least doesn’t seem to use — the <source> tag. This is supposed to be used to provide a link and title of an external reference for the item, but I’m going to take the liberty of misusing it to pass along the location name instead. In my particular case I’m not using it as a link; I just need the text of the location name. But the url attribute is required, so I just stuck the event’s URL in there. (I also added a conditional so this is only inserted on events, not on other post types. But for images I figured it would be a nice bonus to add the featured image across all post types on the site. You may want to add your own conditionals to limit this.)

Here we go:

function my_rss_modify_item() {

global $post;

// Add featured image

$uploads = wp_upload_dir();

if (has_post_thumbnail($post->ID)) {

$thumbnail = wp_get_attachment_image_src(get_post_thumbnail_id($post->ID), ‘thumbnail’);

$image = $thumbnail[0];

$ext = pathinfo($image, PATHINFO_EXTENSION);

$mime = ($ext == ‘jpg’) ? ‘image/jpeg’ : ‘image/’ . $ext;

$path = $uploads[‘basedir’] . substr($image, (strpos($image, ‘/uploads’) + strlen(‘/uploads’)));

$size = filesize($path);

echo ‘<enclosure url=”‘ . esc_url($image) . ‘” length=”‘ . intval($size) . ‘” type=”‘ . esc_attr($mime) . ‘” />’ . “\n”;

}

// Add event location (fudged into the <source> tag)

if ($post->post_type == ‘tribe_events’) {

if ($location = strip_tags(tribe_get_venue($post->ID))) {

echo ‘<source url=”‘ . get_permalink($post->ID) . ‘”>’ . $location . ‘</source>’;

}

}

}

add_action(‘rss2_item’,’my_rss_modify_item’);

You might be able to find a more efficient way of obtaining the $path value… to be honest I was getting a bit fatigued by this point in the process! But it works. You really only need that value anyway in order to fill in the length attribute, and apparently that value doesn’t even need to be correct, it just needs to be there for the XML to validate. So maybe you can try leaving it out entirely.

Put it in MailChimp!

OK… I’m not going to tell you how to set up an RSS Campaign in MailChimp. I already linked to their docs. But I will tell you how to customize the template to include these nice new features you’ve added to your RSS feed.

Edit the campaign, and once you’re in the Campaign Builder, place an RSS Items block, then click on it to open the editor on the right side. Set the dropdown to Custom, which will reveal a WYSIWYG editor full of a bunch of special tags that dynamically insert RSS content into the layout. For the most part you can edit everything here… except for the image. You’re going to have to insert one of these tags into the src attribute of the HTML <img> tag. That requires going into the raw code view, which you can access by clicking the <> button in the WYSIWYG editor’s toolbar.

A few key tags:

*|RSSITEM:ENCLOSURE_URL|*

This is your code for the URL of the image. Yes, it has to be put into the src attribute of the <img> tag directly. There’s not a way that I could find to get MailChimp to recognize an <enclosure> as being an image and display it inline.

*|RSSITEM:SOURCE_TITLE|*

This will display the location name, if you added it to the <source> tag.

*|RSSITEM:DATE:F j - g:i a|*

I just though I’d point this out: you can customize the way MailChimp shows an event date by inserting a colon and a standard PHP date format into the *|RSSITEM:DATE|* tag. Nice!

If you’re interested in a nice layout with the featured image left aligned and the event info next to it, here’s something you can work with. Paste this in its entirety into the WYSIWYG editor’s raw code view in place of whatever you have in there now. Yes, inline CSS… welcome to HTML email!

*|RSSITEMS:|*

<div style=”clear: both; padding-bottom: 1em;”>

<img src=”*|RSSITEM:ENCLOSURE_URL|*” style=”display: block; float: left; padding-right: 1em; width: 100px; height: 100px;” />

<h2 class=”mc-toc-title” style=”text-align: left;”><a href=”*|RSSITEM:URL|*” target=”_blank”>*|RSSITEM:TITLE|*</a></h2>

<div style=”text-align: left;”><strong>*|RSSITEM:DATE:F j – g:i a|*</strong><br />

*|RSSITEM:SOURCE_TITLE|*</div>

<div style=”clear: both; content: ”; display: table;”> </div>

</div>

*|END:RSSITEMS|*

Update! I have encapsulated this functionality, along with some configuration options, into a plugin. You can download it from the WordPress Plugin Directory.