And my cover of Herbie Hancock’s “Sly” is featured in the “Sex Ed” episode of the Risk! podcast.

I’ve also made a YouTube playlist of all of the videos from the album.

And my cover of Herbie Hancock’s “Sly” is featured in the “Sex Ed” episode of the Risk! podcast.

I’ve also made a YouTube playlist of all of the videos from the album.

A little over a week ago I did something really stupid. Today I took the final step in making amends for that error, which was ultimately the consequence of a questionable decision I made many years ago, to create an ad hoc WordPress multisite setup. That lowercase “m” is significant, and I hinted at it in the post I linked to above.

This was not a proper WordPress Multisite setup. I think that feature probably already existed at the time, although it may not have. This was my own concoction, created by adding a PHP switch to the wp-config.php file, telling it to use a different database and uploads directory depending on the domain name in the HTTP request. It allowed me to manage a number of my own and Sara’s websites with a single WordPress installation, but it was dangerous.

None of the sites “knew” about each other. That wasn’t really a problem, except when it came to managing themes and plugins. I always had to be careful to remember that just because my site wasn’t using a particular theme or plugin, didn’t mean one of Sara’s sites wasn’t… or even one of my own other sites in the setup.

I forgot about that little detail when I did my stupid thing a couple weeks ago. I deleted all of the themes my blog wasn’t using, forgetting that Sara was using many of them. In a panic to quickly restore the themes, I made matters worse by accidentally restoring the entire server from a 6-day-old backup, erasing all of the work Sara and I had done on our respective sites over the preceding week.

My “final step” in making amends was to at least remove my own sites from that setup, so it is now just running Sara’s sites. If you’re reading this, it means you’re seeing my blog in its new home. (Coincidentally, this is also facilitating my gradual transition away from Digital Ocean in favor of Linode for my hosting needs.) I also moved my John Coltrane and Adelia Haight McCormick sites, which were part of the same cockamamie arrangement.

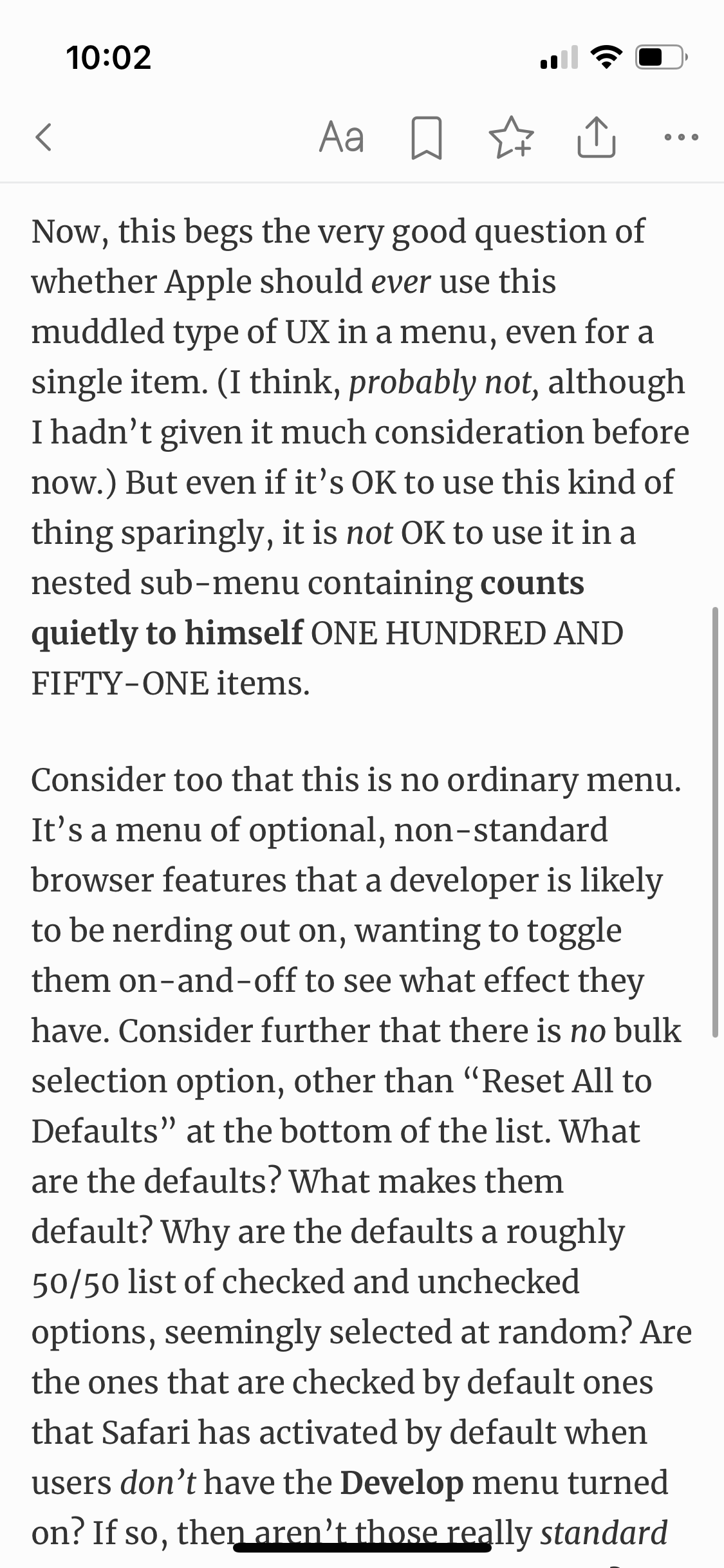

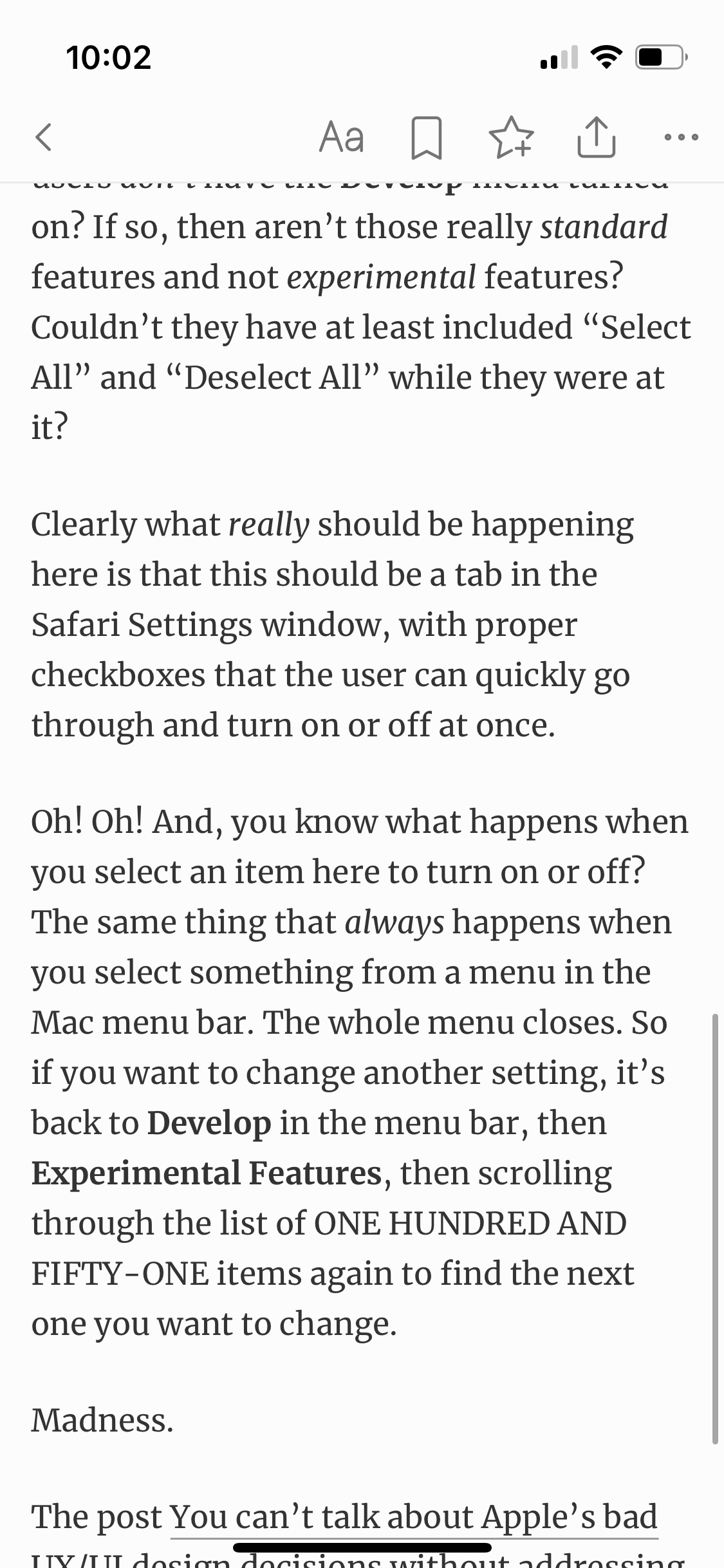

One last thing that I didn’t think I’d be able to recover: I wrote two fairly substantial blog posts in that week, and I was pretty sure those were gone forever. But last night I discovered that the Feedly app on my iPhone still had them cached! I quickly snapped a series of screenshots so they wouldn’t be lost forever.

I had originally intended to retype them here, back dating them to their original post dates, to make it seem like they’d never been lost. But somehow it seems more fitting to just post those phone screenshots instead.

One of the posts hinged on a composite Mac screenshot I had taken from Safari, demonstrating its absurd Experimental Features menu, and that’s an image I still had on my Mac, so I’m including it below as well.

Enjoy.

Also worth noting here… this is my first post on this blog using the Block Editor, a.k.a. Gutenberg. I’ve finally accepted its inevitability. I’ll probably update the site to a new theme in 2023 as well… this one is a custom hack of Twenty Eleven, for cryin’ out loud!

I’m an early adopter for a lot of things, but new versions of PHP are generally not one of them. PHP 8.1 wasn’t really on my radar until I set up a new server running Ubuntu Linux 22.04, where PHP 8.1 is the default version.

Yeah, I’m a commercial WordPress plugin developer too, but my business is small. It’s easy to understand me not being 100% on top of this.

What I do not understand is how huge WordPress plugins like Jetpack, WooCommerce and Wordfence can get away with not being on top of it.

The general response these developers are giving when questioned on this is, “they’re only deprecation notices, everything should still be working.” Which is true.

But.

Are you a developer? Do you ever need to turn debugging on? Have you seen what happens when you have multiple plugins active, each of which generates 5-10 PHP deprecation notices on every page when debugging is turned on?

Aside from making the site, and especially the WordPress backend, borderline-to-entirely unusable (which, honestly, is a bigger problem than what I’m about to say), it also makes normal debugging impossible. It’s hard to find real issues when you have to wade through more than a screen’s worth of irrelevant deprecation notices. And the sheer volume of the notices breaks page layouts to a point where it’s impossible even to know what is or isn’t broken.

I actually blame PHP for this. I don’t know what they were thinking with some of these changes that are triggering all of the deprecation notices. I know “real” programming languages aren’t as loosely typed and lenient with sloppy coding as PHP is, but… well, it’s kind of too late to put that genie back in the bottle. I haven’t bothered to investigate exactly what the rationale is for no longer allowing null input to string handling functions. What I do know is that there’s a ton of code out there, written by competent, experienced developers, that is now triggering these warnings, because until now it was always fine to equate null and an empty string.

Anyway, principled arguments aside, I have a more practical frustration to deal with right now… I’m finding it hard to do my work, because other people haven’t done theirs.

What are your thoughts on Dolby Atmos?

More specifically: what are your thoughts on Apple Music automatically playing songs in Dolby Atmos through laptop speakers?

My MacBook Pro has pretty great speakers (for built-in laptop speakers). I’m sitting here listening to Talking Heads’ Fear of Music, and I could tell immediately that there was some kind of surround effect going on. It was very disorienting — it created a physical sensation in my ears and almost started to give me a headache. Then I realized I could turn it off and instantly everything went back to normal.

I’m not entirely sure what kind of dark magic Dolby is employing with this (I’m sure it has something to do with reversing the polarity of the stereo channels or something nerdy like that), but I don’t understand why it’s being foisted upon us. It reminds me of the trend about a decade ago of every movie being made in 3-D, and even 3-D TVs that no one wanted. Eventually they caught on to the “no one wanted” part and now it’s not much of a thing. I hope Dolby Atmos on streaming services follows in short order!

Related: Why Your Atmos Mix Will Sound Different On Apple Music

My plans for this album project have ping-ponged around wildly in the 2 years since I first started planning Volume 3 of my Northern Daydream series.

Finally midway through 2022 things started to come into focus, with an emphasis on two vitally important but radically different jazz pianists who both hit their creative stride in the late 1960s and early 1970s: Herbie Hancock and Keith Jarrett.

But even as I began to see that this album needed to have a “Side H” and a “Side K,” I waffled on exactly which songs I wanted to cover, and how I wanted to approach them.

Finally, with yesterday’s accomplishment of “KJ3M” — a 10-minute suite featuring three distinct Keith Jarrett compositions, stitched together with three brief keyboard improvisations, inspired by Jarrett’s own concert style, the project has reached its conclusion.

I had not planned to record any of these three songs when I laid out the project. I hadn’t even heard any of them at that point, honestly. But once I did hear them, I knew I needed to make them the focal point of the conclusion of the project.

“Mortgage On My Soul” and “Common Mama” are an interesting pair. Both are built over a similar bass ostinato — in the same key, no less — and could actually be ripe for a mashup. But I decided that was not the right treatment. I wanted to show the ways the two are different, not the ways they are alike. (Whereas you might see the result of this project overall as showing the ways Jarrett and Hancock are similar even though on a surface level their styles are very different.)

“The Magician In You” kind of came out of left field. It immediately follows “Common Mama” on Jarrett’s 1972 album Expectations, and I really like the pairing. After spending several minutes in a harmonically static, groove-based mode, it’s very satisfying to bask in the rich harmonic textures of this rock/gospel ballad.

I played up the harmonic structure here in ways I kind of wish the original had done, although I know Keith Jarrett’s style, especially at that time, was to leave listeners with only the slightest hints of the true structure underneath, allowing improvisatory group interplay to constantly pull at the loose threads of more predictable musical forms. I don’t slight him for it at all, and yet the composition is just so good that I want to get absorbed in it and let it carry me away.

And this is part of why I’ve decided to wrap up this project here. I’m ready to take on new challenges, including attempting to create a big band arrangement of “The Magician In You” that builds on the elements I put into this version. So, this probably means I will step away from spending 18+ hours on a Saturday, twice a month, on an epic recording/video production session. For a while, anyway.

Here’s “KJ3M”:

And you can listen to — and watch — the entire album here.

Once I’m satisfied that the mixes for the album are final, I’ll post another update with download links. Stay tuned!