I’ve been using Advanced Custom Fields Pro since it was a solo project run by Elliot Condon. When you contacted ACF for support, you dealt with Elliot directly. I still think of it that way, even though several years ago, Elliot (after growing the business apparently beyond the scale he was interested in managing) sold ACF to WordPress plugin company Delicious Brains, which itself was later acquired by WP Engine.

Make no mistake: for me and countless other developers, ACF is the reason we can use WordPress as a general purpose Content Management System (CMS). It’s the reason I stopped building my own custom CakePHP-based CMS!

WordPress started as blogging software, and based on all available evidence, the core team, or really its BDFL, Matt Mullenweg, still sees it that way. I suspect it burns Matt up inside that a large contingent of us developers who have made WordPress the most popular CMS in the world only use WordPress because ACF makes it possible, and that we’re using WordPress specifically in ways he never envisioned it being used.

I doubt Matt’s ongoing war against WP Engine is that much about ACF. But it’s unmistakable that with WordPress.org’s (read: Matt’s) recent hostile takeover (don’t call it a fork, because this isn’t how forks work) of the free version of Advanced Custom Fields, renamed to “Secure Custom Fields,” and their even more recent actual fork of the paid Advanced Custom Fields Pro, also confusingly renamed to “Secure Custom Fields” and released for free in the Plugin Directory, WP.org/Matt sees ACF as, at least, a useful pawn in that war.

The thing that really confused me though was how could they get away with it? Advanced Custom Fields Pro is a paid plugin, distributed directly on its own website, to paying customers only.

In order to appear in the WordPress Plugin Directory, plugins are required to carry an open source license, with GPL v2 being the preferred choice. The free version of ACF in the Plugin Directory is, of course, GPL. But the Pro version…?

Strangely, after the news broke about this, I started seeing counterarguments that WP.org absolutely had the right to do it, because there wasn’t any other copyright in the ACF Pro code.

What?

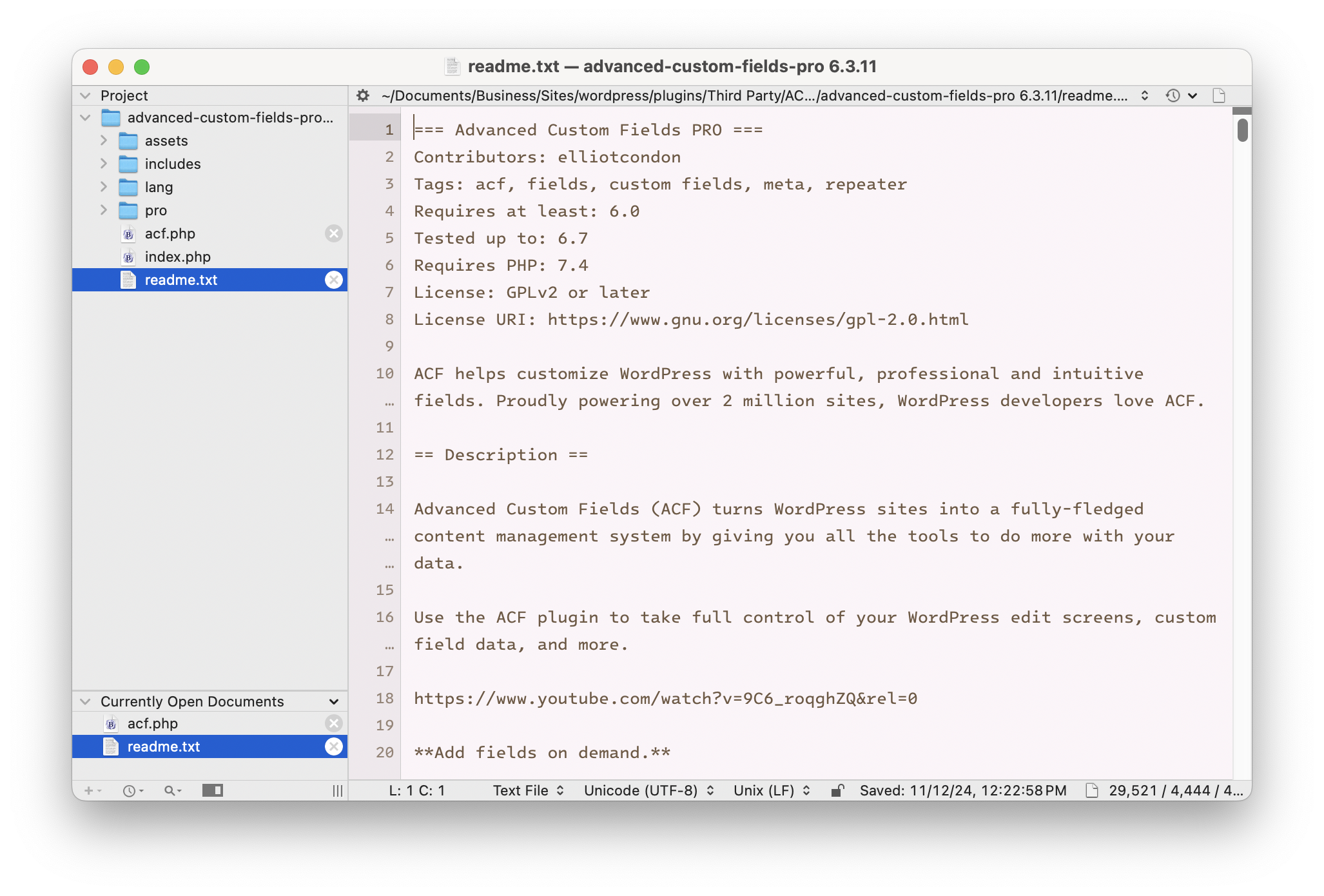

So I checked for myself. Standard practice in WordPress plugins is for the license terms to be included in either the readme.txt file, the plugin’s main PHP file, or both. Here’s the top of the readme.txt file in the latest version of ACF Pro (6.3.11):

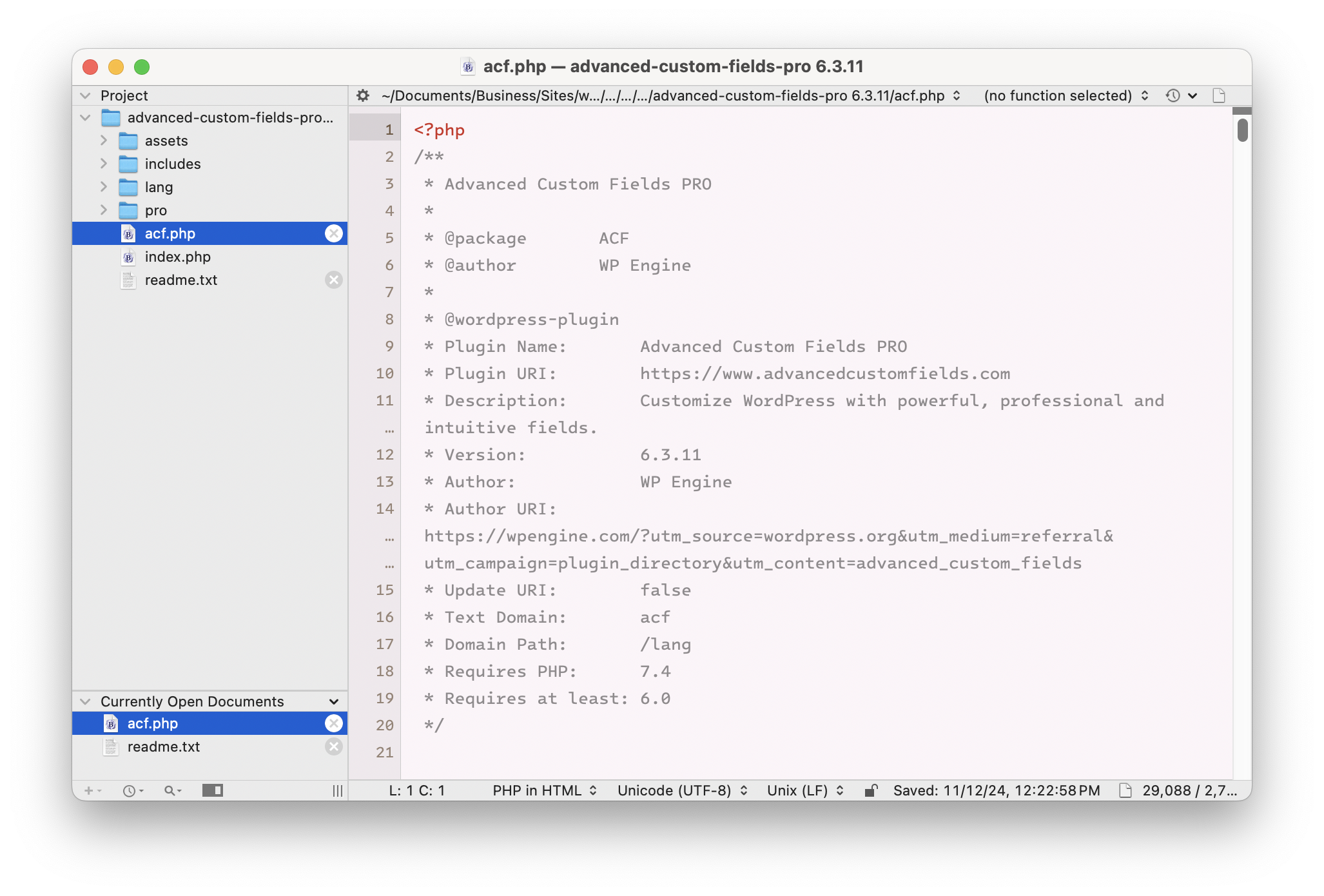

Well, there it is. ACF Pro is GPL v2. But just to make sure we didn’t miss anything, here’s what’s in the main PHP file:

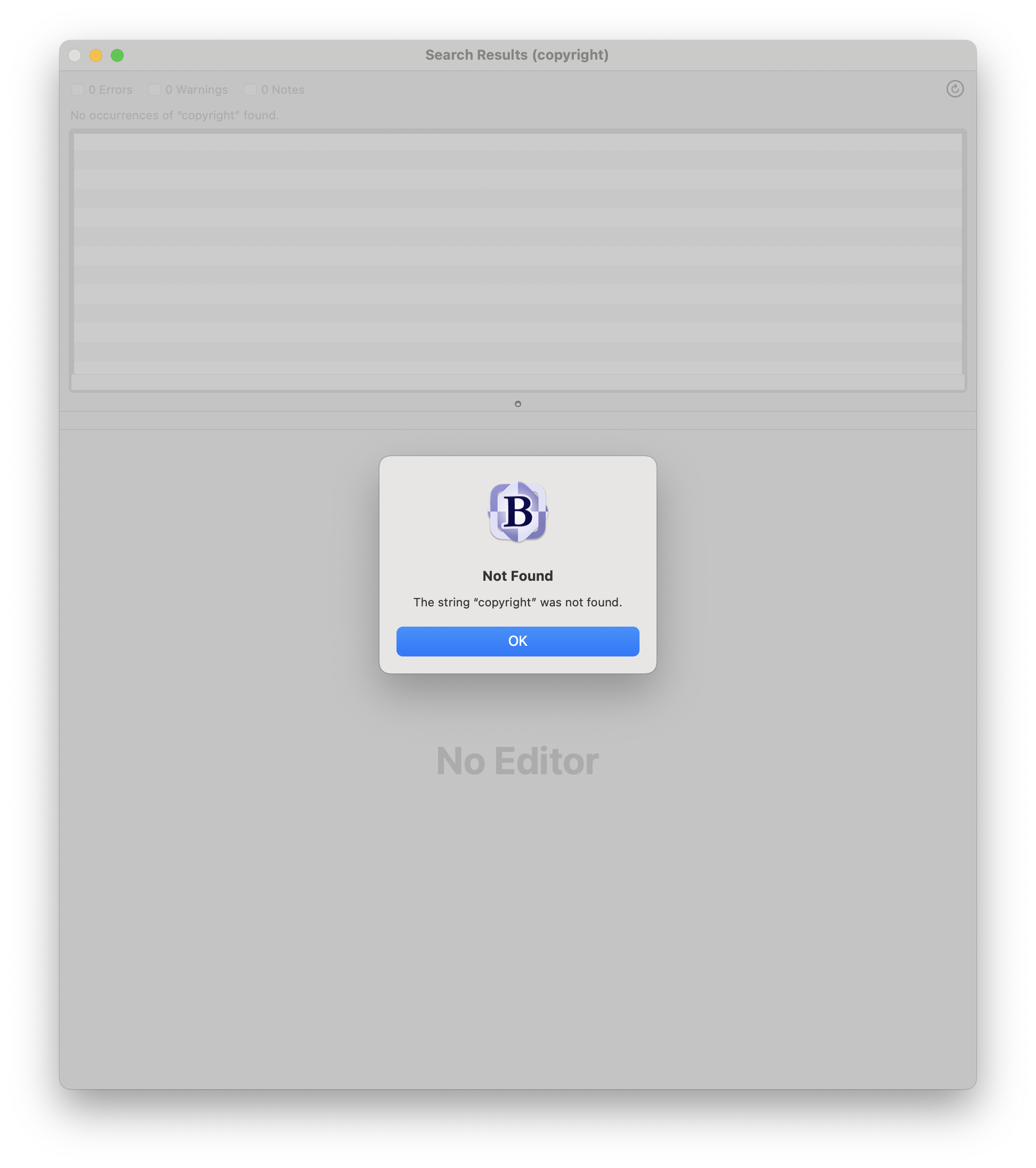

I did a multi-file search in the plugin code for any instance of the word “copyright” and came up empty.

Well, that’s not good.

In case you’re not familiar with the GPL/open source, uhhh… yeah. This says in effect that WP.org absolutely has the legal right to fork and freely distribute not just the free version of Advanced Custom Fields, but the paid Pro version as well.

But just because it’s legal, doesn’t mean it’s ethical. And reading pages of the ACF site such as their terms for embedding ACF Pro in other plugins and themes, it is clear that their intentions, while generous, are more restrictive than the GPL.

I’m not really sure how, in all of these years, it never occurred to Elliot, or Delicious Brains, or WP Engine, that they needed to change the license terms for Advanced Custom Fields Pro. There’s nothing to stop them from doing that. Earlier versions of the plugin released under GPL will always be GPL. But newer versions could have switched to a more restrictive copyright, which would have (legally) prevented WP.org from forking ACF Pro.

As it happens, I now find myself somewhat in the position Elliot Condon was in back when I first started using Advanced Custom Fields Pro over a decade ago: a solo developer of a plugin that has both a free version in the Plugin Directory, and a paid Pro version.

My plugin is far more niche than ACF, so I doubt it will ever be valuable enough for a company like Delicious Brains to snap up, or that any company that would snap it up would itself become valuable enough to be acquired by a hosting behemoth like WP Engine.

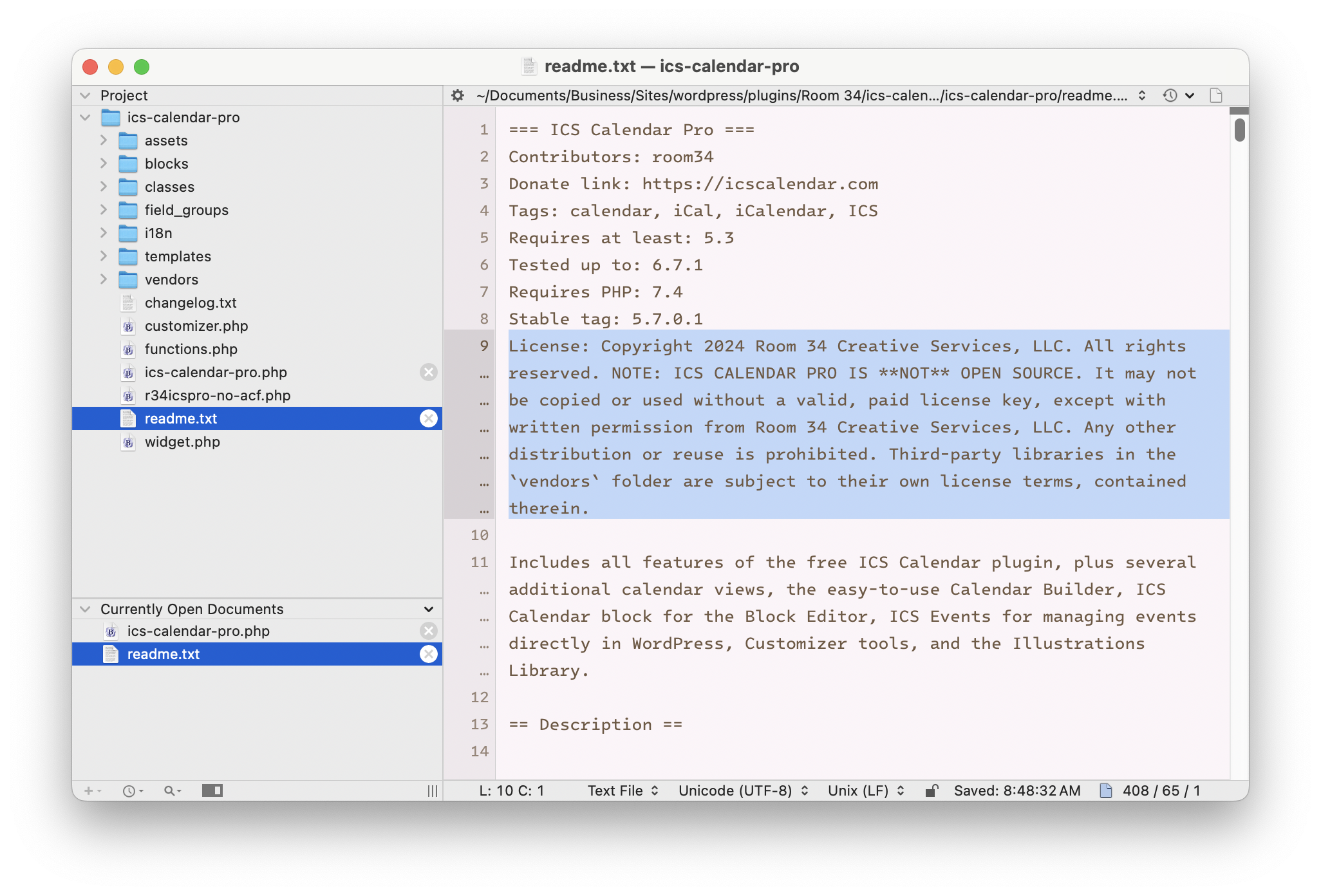

I’m less valuable than a pawn. But that doesn’t mean my work isn’t of value to me. And that’s why, although the free version of ICS Calendar in the Plugin Directory — by necessity — carries a GPL license, the Pro version emphatically does not. (The latest version’s terms were reworded in the wake of this situation to be even more emphatic.)

Update: After posting this, I read the terms of the GPL more closely, and I think the issue may be that, because ACF Pro is coded in such a way that the free version’s code is deeply integrated with the Pro code, they may legally have no choice but to make ACF Pro GPL as well.

I believe it is within the terms of the GPL, and is fairly common practice among paid plugins (including mine), to put any GPL code libraries into a vendors (or similar) folder, and keep the proprietary code separate. (That’s how ICS Calendar Pro works.)

Since the GPL was written with full operating systems in mind, interpreting its wording in the context of something like a WordPress plugin, which doesn’t exist in compiled form and can’t function outside of a much larger system, can get a little fuzzy. What can or can’t be included in that vendors folder?

This leads to a broader consideration: Do I believe in the principles of open source? Or am I just using open source software opportunistically? Can I both support and contribute to open source and make money off of my software, even if it relies (partially) on other people’s open source projects to function?

I think it is naive to suggest anyone who is actually making a living working with open source software is not in that compromised position. Automattic (Matt’s company) relies on open source software just as much as WP Engine, and does far more to blur the lines between the free and commercial sides of the WordPress ecosystem than WP Engine does. (WordPress.com, anyone?)

There is no money in pure open source. That’s kind of the point. But even the most ardent anti-capitalist still needs money to survive in any modern society. And that money has to come from somewhere, whether that’s working for a for-profit company that benevolently “gives back” to the open source community by committing employee time to working on open source projects, or from indie developers releasing the basic versions of their software for free and selling paid “premium” add-ons to provide a source of income.