Every time I run into another weird, seemingly illogical quirk of the process of building a WordPress theme with Block Editor (a.k.a. “Gutenberg”) support, I ask myself the same question: How is this better?

As time goes by, the answer is starting to come into focus. Unfortunately, it’s not entirely satisfying.

Here’s what I’ve learned so far.

How is this better than what came before?

Well… what came before? You can’t ask the former without first answering the latter.

Over the years, WordPress has become many, many different things to different people. So you can’t expect the Block Editor/Gutenberg to be universally better (or worse) than what it’s replacing, because it’s replacing so many different things.

Is it better than the various “page builder” plugins out there? I’m looking at you, Elementor, Divi, Beaver Builder, and WPBakery, among others.

Honestly, I loathe every last one of these page builder plugins. Partly that’s because before I worked primarily with WordPress, I rolled my own CMSes for years, dating back to the pre-.NET Microsoft era of ASP talking to a SQL Server 7.0 database. Then I moved to MySQL and PHP, first building a completely custom system before any MVC frameworks existed, followed by several years of development on a fairly robust custom CMS based on the CakePHP framework. I was very proud of that work, but by 2014 it was clear WordPress (which I had used for my own blog and occasional client projects since 2006) was picking up enough steam as a general-purpose CMS that my own couldn’t keep up, and I took the WP plunge.

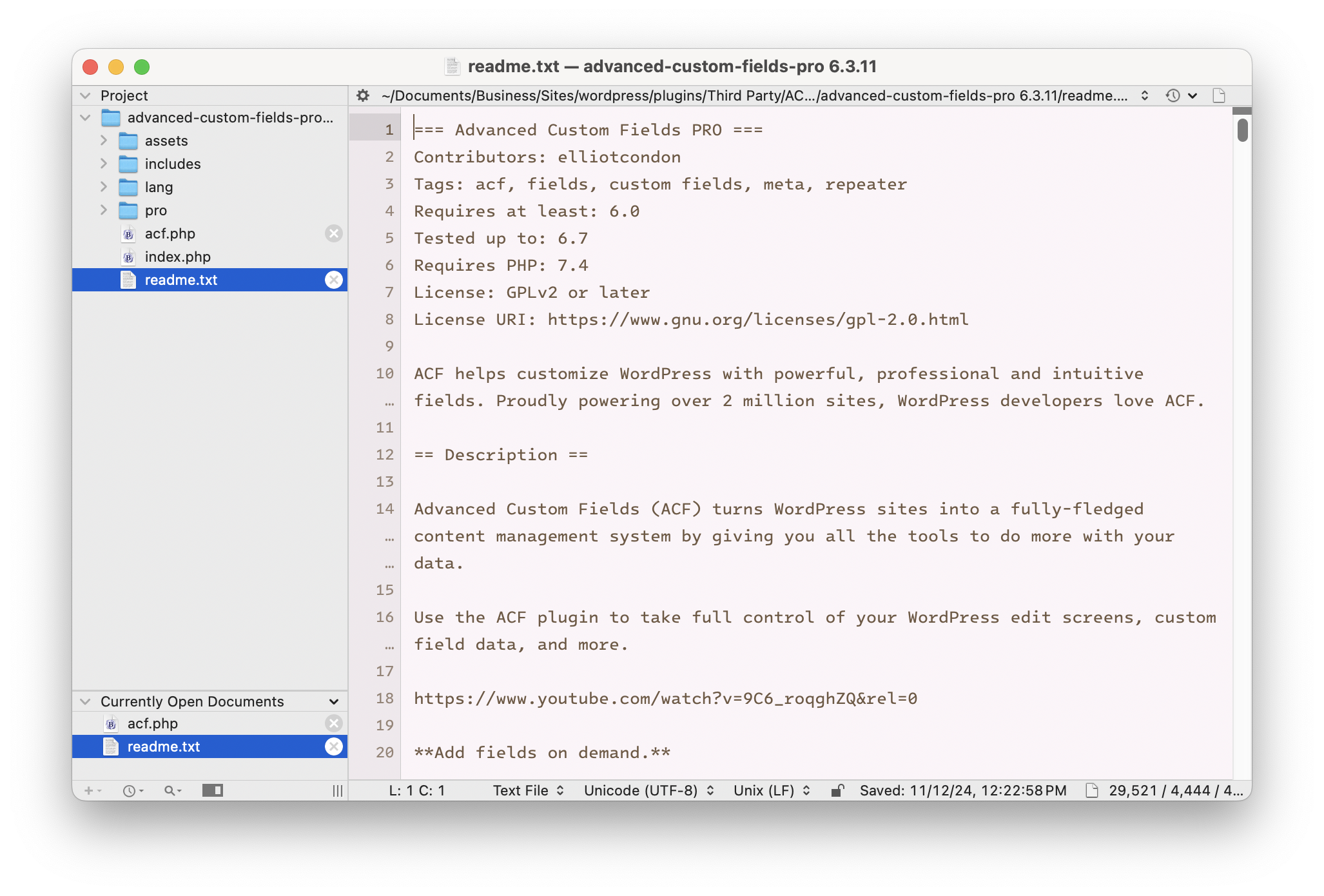

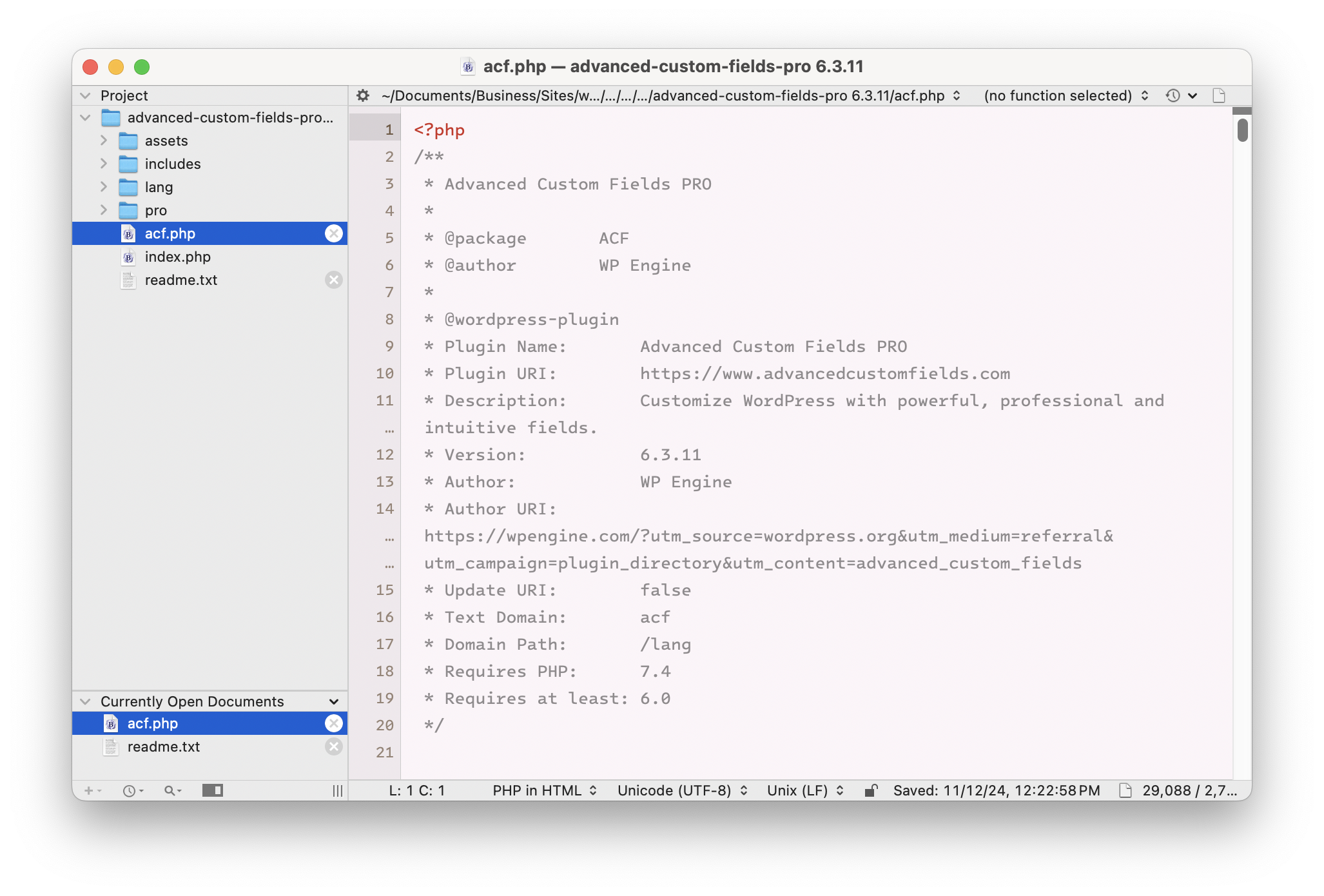

Almost immediately, I wholeheartedly embraced Advanced Custom Fields as my solution to extend WordPress. And, in particular, I used its Flexible Content fields to create my own Block Editor-style interface, years before Gutenberg existed.

It’s way better than page builders.

But it’s also not entirely “the WordPress way.” It’s way more “the way” than Elementor and its ilk, but still… it led to a situation where all page content on my sites is stored in the wp_postmeta table, which is not ideal, for many reasons.

What’s good about the Block Editor?

I absolutely, 100% prefer the Block Editor/Gutenberg over the popular page builder plugins. It’s a much cleaner, faster, more intuitive user experience, and it renders front-end pages quickly. It’s built in which is a benefit in and of itself. But honestly, it only feels built in because WordPress is changing itself to be more like Gutenberg, rather than Gutenberg being built to feel like the WordPress we know and love.

Aesthetically, I like the Block Editor. For usability… well, where do I begin? I’m an old fart who still expects all of the available options to be visible on-screen, not just “discoverable” if I happen to hover my mouse in the right spot. And I’m a lot more savvy to this new type of interface than most of my clients, so I struggle to understand how the WordPress core team thinks this is an optimal approach. (OK, so maybe this paragraph belongs in the “bad” section below.)

But that leads me to the best thing about the Block Editor, which is not inherently great. It is what it is. I don’t mean that as the empty cliché we hear a thousand times in every business meeting or reality show interview. I mean it literally: The Block Editor is WordPress now. There’s no going back. So while that may mean some growing pains and struggles, it also does mean that it will (probably) continue to get better over time, and unless it is an absolute failure, WordPress will continue to grow, which means it will always continue to receive support.

What’s bad about the Block Editor?

This is another one that really depends on your perspective: where you’re coming from, what you’re used to, what role you play in the creation of a website.

If you’re a content editor who is a capable system user but not a developer/UI designer, and you’re used to the “vanilla,” TinyMCE-based WordPress classic editor, there’s a very high probability that you will be confused, overwhelmed, and/or frustrated by the Block Editor, because the concept of “blocks” does not reveal itself in the most optimal way as you are discovering it. (I’m not sure what the most optimal way is, but I’m confident this isn’t it.) I will say, however, that the glitchy, wonky, invasive behavior of earlier iterations of Gutenberg has almost entirely been smoothed out.

On the other hand, if you’re that same content editor, but you’ve been forced in the past to work with Elementor, Divi, Beaver Builder, WPBakery, or something similar (and, if you have, I’m almost certain you hate it, based on anecdotal observations), then I think there’s a good chance you will love the Block Editor, at least if you’re given the opportunity to experience it in its pure form, not something that’s been bastardized the way those aforementioned plugins destroyed the classic editor.

But me? I’m a developer. Although I obviously spend a fair bit of time using the editor to test my work and also to assist in initial content loading on new sites, I mainly work behind the scenes, in code. And this is where I struggle mightily to understand just what the hell were they thinking??? with some of the decisions that went into how the Block Editor functions at a code level.

What’s it like to code for the Block Editor?

There are two main ways in which building Block Themes and/or coding for the Block Editor differ greatly from the “classic” way WordPress has functioned up to this point.

First, at a more surface level — in fact, it’s a level you can even stumble upon in the Block Editor itself if you click the right (wrong?) button — there’s the block markup, and how it gets stored in the database.

There is something that is absolute genius about this. In fact, conceptually it’s probably the biggest Eureka! moment of the entire Gutenberg project. All of the meta data about each block is just HTML comments. That means that all of the actual content of a page/post built with the Block Editor is stored where it should be in the database: in the post_content field of the wp_posts table.

This is much better than the way Advanced Custom Fields works. It’s fewer database queries, so it’s faster, and it’s where the content “belongs” so it’s automatically handled correctly by plugins — anything from Relevanssi for custom site search tools, to Yoast SEO for search engine optimization. (OK, those are both search-related, but in very different ways.) And the use of HTML comments for the meta data means it’s even backwards compatible: if the content gets loaded in a theme that doesn’t support the Block Editor, it may not look exactly right, but your content will at least still be on the page, in its entirety.

The problem is, the code itself is kind of a mess. I like the idea of using HTML comments to store the block meta data, and I like the use of JSON as the format for the properties.

But it often ends up being a lot of code, which is messy if you ever need to look “under the hood.”

And it’s fairly brittle, so if you edit any of it directly, you’re probably going to break it, and at this point the Block Editor only has middling success at recovering “broken” blocks.

And the documentation so far is woefully lacking. I know only too well how hard it is to make the time to write proper documentation, but when you’re forcing a change this radical on a user base this large, you need to prioritize it.

And worst of all, all of that JSON code is really only to get the editor to “remember” the settings for the block when you go to edit it. Most of the details also have to be repeated in the class attribute for the container HTML element in order to actually render anything stylistically in the page. (Once again, I don’t really know the optimal solution, but this isn’t it.)

And. And. And. And. And. (Sorry, wrong software, but since it’s timely I thought I’d throw it in there to amuse myself when I re-read this post in a few years.)

OK, all of that was only the first way the Block Editor differs greatly from the classic WordPress developer experience. The other way is the template structures that go into a theme.

I’m pretty flexible about how code files should be organized, as long as they are organized. Each project is unique, and as long as it has a consistent internal structure, it doesn’t have to be the same as every other one. I know this attitude is somewhat heretical in certain circles, and honestly the fact that WordPress has heretofore been just as flexible has created a lot of headaches for people trying to understand how themes, plugins and the WordPress core interact. It can also make it exceedingly difficult to jump into a custom theme someone else built and figure out where the hell everything is.

I get it. And I appreciate the core team’s efforts to impose a new, consistent structure that reinvents the way WordPress themes are built, and that aligns with how the Block Editor works.

I also get that it was not just an arbitrary decision to build the Block Editor on React. The Block Editor needs to be dynamic in a way the classic editor is not, so a purely PHP-based interface would not work. Not even something using the already-present jQuery would do the trick.

But building the Block Editor on React requires developers to know or learn React. I’m all for people learning new skills and adapting with the times (even though I haven’t bothered to learn React yet), but it’s a tall order to force an entire development ecosystem to radically shift gears.

That’s not even my biggest criticism though. What really bothers me about the new Block Theme template structure is the move away from PHP in areas where server-side scripting clearly offers some major benefits, with only the most nebulous justifications for the change. It usually comes down to “PHP is too intimidating to users,” but I find that really hard to accept, because PHP is much easier to learn, especially to a “dabbler” level, than React, and it’s way more forgiving than JSON.

So far my work on a new Block Theme hasn’t even touched React (partly thanks to my good old friend, Advanced Custom Fields). I’m coming around to the theme.json file, the more I work with it. I still want to be able to use PHP to dynamically set site properties, but I’m learning, little by little, how to accomplish my goals without it. (Or, perhaps, I’m changing those goals to suit the new platform.) I’m also slowly coming to understand that theme.json is mostly just for generating the inline CSS Gutenberg outputs in the <head> (and some ancillary functionality in the editor itself), and not a comprehensive spot for all manner of site parameters.

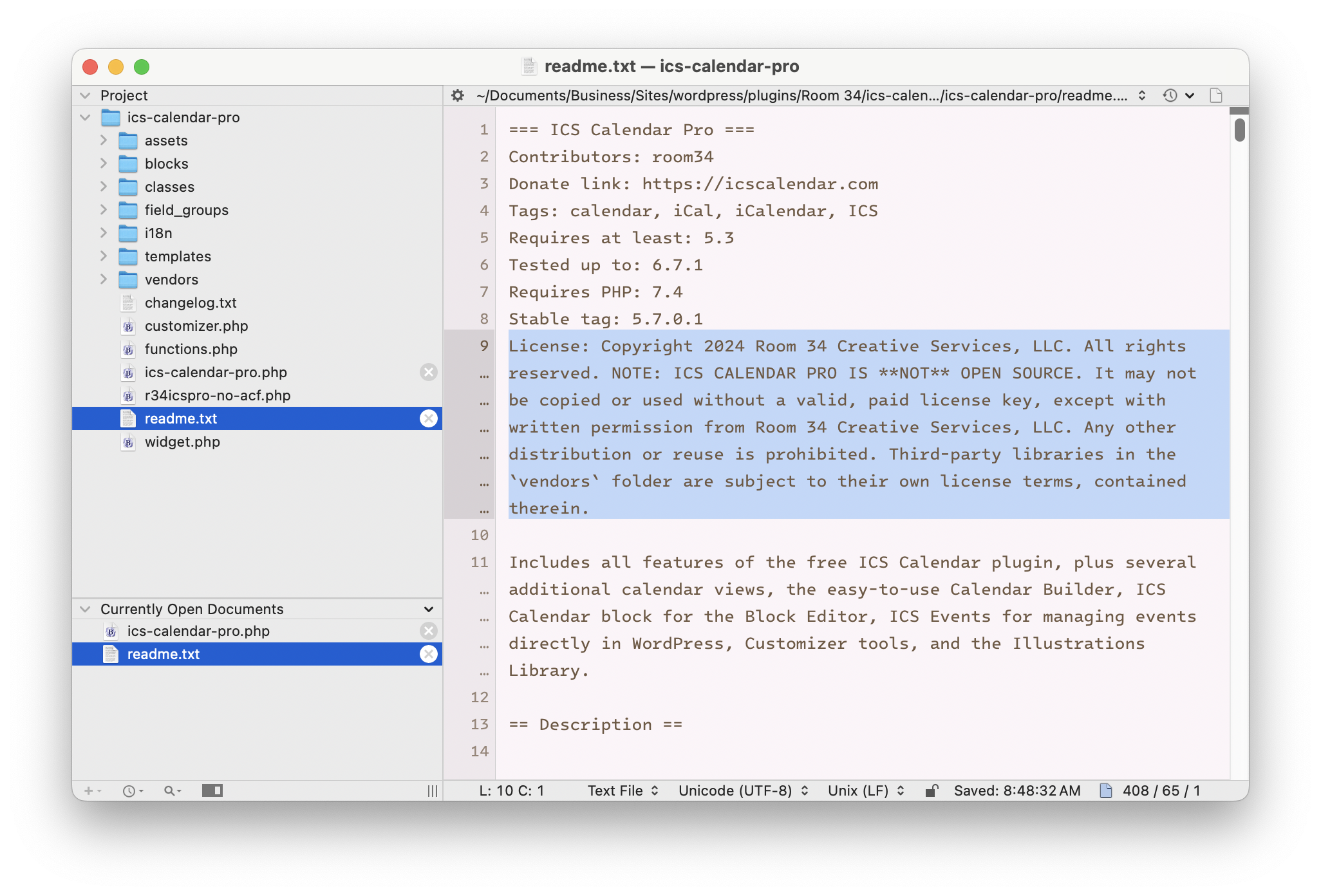

What I really do not understand, and may never accept, however, is the decision to make the files in the templates folder plain HTML files instead of PHP. In fact, my struggles with this very issue are what prompted this entire rant.

How do I use translation functions on hardcoded text in the templates, without PHP?

How do I selectively display post meta data — like author, publish date, and taxonomies — for posts in the search results template, but not for pages, without PHP?

I don’t have answers to these questions. Yet. But they beg the larger question of why the templates aren’t written in PHP in the first place. Is it a performance thing? That might be justifiable. But the whole “ease of use” argument makes no sense. A person isn’t going to be creating a theme in the first place if they don’t know some PHP.

No, I think it probably all comes down to being a decision that’s part of the development roadmap for Full Site Editing. So the decision is more about what the core team wants than what I want. Fair enough.

Who is this really for?

This is another grand question. Who is the Block Editor really for? Who is WordPress really for? I had never really asked that question, rhetorically or literally, until the Gutenberg project.

WordPress started out as blogging software. But it has since become much more than that. It famously powers somewhere around 40% of the web. Are 40% of websites blogs? In terms of sheer number of sites, maybe. In terms of amount of traffic, definitely not.

WordPress powers everything from the most obscure blog no one but its owner reads (don’t look at me) to massively popular sites that have thousands of simultaneous users. And it’s not just blogs. WordPress may not have been designed to be a general-purpose CMS, nor, in many ways, is it ideally suited to that purpose, but historically it has had the right mix of flexibility, extensibility, ease of use, and low barriers of entry, that it has come to be used for just about any purpose one might imagine a website serving.

But who is it really for?

I’m reminded of the story (recounted by John Gruber on a recent episode of The Talk Show) that Steve Jobs apparently pushed for the creation of the iPhone because he wanted a way to check his email on the toilet. The iPhone is, in the most generous sense, for everyone. But in a particular way that was critical to its actually coming into existence, it was for Steve Jobs and his bathroom correspondence habits.

So again, who is WordPress really for? Who’s making the decisions that ultimately determine what goes into it, that define what it is? That of course would be the core team, and probably more than anyone, the leader of the core team, Matt Mullenweg. I don’t know much about Matt, other than that he spearheaded the initial WordPress project (at least once it was forked from b2), that he now runs the semi-eponymous Automattic, and that we most likely have very different senses of humor. (Consider this: I’ve written a plugin that partly exists to remove humor/”folksiness” baked into WordPress that I am pretty sure is attributable to Matt.)

Matt still leads the core team, and has final say on certain decisions about its direction. Ultimately, if he thinks something matters for WordPress, it makes it in. And he clearly believes WordPress is still primarily, if not entirely, for blogging.

Again, maybe in terms of number of sites, “most” WordPress sites are straight-up personal blogs. But in terms of an active ecosystem, a development community of people who are able to make a living building WordPress sites, who comprise a thriving professional industry, in my experience, at least, blogging is peripheral or absent entirely from most professional applications of WordPress. It’s a general-purpose CMS, first and foremost, even if that’s not what it was originally intended to be. And, sadly, even if that’s still not what its core development team prioritizes.

I don’t know. I’m just me. A solo, somewhat iconoclastic developer who likes to do things their own way. I’ll probably never embrace putting spaces inside the parentheses in my PHP code, and I definitely won’t use if: endif; constructs.

I have strong opinions, but I’m not an idealist.

I just want PHP in my damn templates. Is that too much to ask?

Ironic side note: This site is one of the few cases where I have built a WordPress site that absolutely is a blog, full stop. And it’s not using Gutenberg, because I set up the Classic Editor plugin on it ages ago. But as I write and edit this post, I’m actually finding myself wishing I had the site running Gutenberg instead of switching between the back end and the front end. Of course, that’s because I always write my posts in plain HTML rather than the visual editor. I said I’m an old fart.